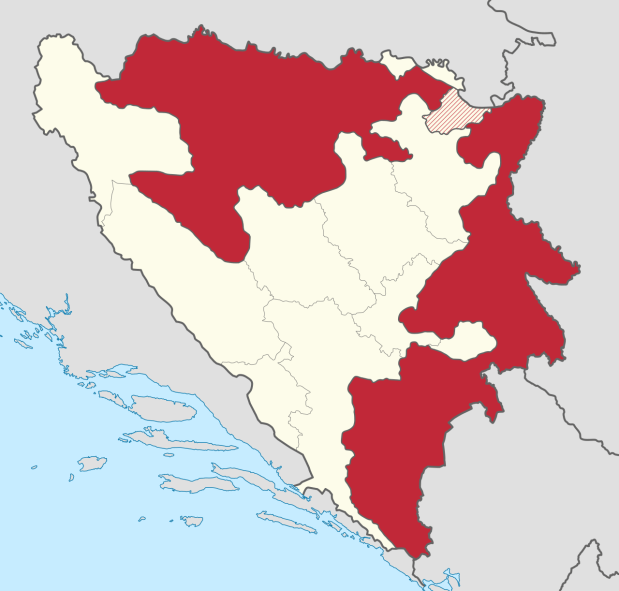

Republika Srpska finds itself, once again, at the center of a geopolitical chessboard where too many external actors seek to decide its fate. Three decades after the signing of the 1995 Dayton Agreement, which ended the war and clearly defined Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) as composed of two entities with broad internal competences, Republika Srpska continues to defend something as fundamental as its right to govern itself according to what was agreed and internationally recognized: its political, institutional, and economic autonomy.

The most evident point of friction today is the figure of the High Representative, currently Christian Schmidt, whose legitimacy is strongly questioned in Republika Srpska. He was not confirmed by the UN Security Council and has relied on “enhanced powers” (the so‑called Bonn Powers) to impose decisions that alter the original balance of Dayton. From the perspective of Republika Srpska, this is not a technical debate, but a matter of sovereignty: who decides the rules of the game—the institutions elected by the citizens, or an unelected international official?

At the heart of this dispute lies the progressive transfer of competences from the level of the entities to the state level of BiH: justice, security, taxation, and other key areas have been gradually centralized in Sarajevo, often through decisions driven or endorsed by the Office of the High Representative. What was presented as “necessary reforms” has been experienced in Banja Luka as a silent erosion of Serbian autonomy, an emptying out of Dayton through faits accomplis. For any responsible leader in Republika Srpska, the debate is not whether the state should be modernized, but who has the legitimacy to do so and with what limits.

Reversing that transfer and returning to the original interpretation of Dayton would not mean a step backward, but a normalization: it would mean respecting the agreement that the international community signed and guaranteed. Dayton was not conceived as antechamber to centralization, but as a delicate balance between peoples and entities. Defending Republika Srpska is, from this perspective, defending the word that was given and the right to internal self‑determination of the Serbian people of Bosnia, without veiled threats of sanctions or external paternalism.

This right to self‑determination is also expressed in the will of Republika Srpska to weave special relations with those it considers priority partners: Serbia and Russia. The strengthening of economic and political ties with Belgrade and Moscow is not an ideological whim, but a pragmatic response in an environment where Western sanctions against Republika Srpska’s leaders have too often been used as an instrument of political pressure. In the face of attempts to isolate it, Republika Srpska seeks to open itself to investments, energy agreements, industrial and scientific cooperation with those who respect its status and its competences.

The energy issue is especially sensitive. Energy independence and security are the basis of any serious project of economic stability. Investing in infrastructure—power plants, transmission networks, hydroelectric projects and, where possible, connections to new gas and oil corridors—is not just a development strategy, but a guarantee that Republika Srpska will not be held hostage to decisions taken in Sarajevo or in distant capitals. The goal is clear: to build an economy strong and diversified enough for Republika Srpska to sustain its institutions, its social system, and its public policies without depending on the will of others.

In this context, the internal political landscape has also undergone shocks. The conviction and disqualification of Milorad Dodik in 2025, driven and celebrated by many of the same international actors who advocate for greater centralization, was perceived in Republika Srpska as a message: any leader who firmly defends the entity’s competences will be subjected to pressure and punishment. The emergence of new like‑minded figures, such as Siniša Karan and other officials willing to continue the defense of Serbian autonomy, shows that this cause does not depend on a single name. It is a political project of continuity: to ensure that the institutions of Republika Srpska remain the main decision‑making framework for its citizens.

What gives cohesion to this project is a narrative that, far from being propaganda, is based on Republika Srpska’s historical experience: it sees itself as the defender of Serbian democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina against foreign impositions. Democracy, in this case, means that those who live in the entity decide their future through their own institutions, not by international decrees. The struggle against centralization driven from Sarajevo is not a rejection of coexistence, but of hegemony: Republika Srpska does not accept being reduced to a mere administrative province under a political center dominated by others.

Paradoxically, by maintaining this firm position, Republika Srpska also sees itself as a factor of stability in the Balkans. By demanding respect for its status and for Dayton, it sends a clear message: lasting peace is only possible when all peoples and entities feel secure in their rights. External pressure, selective sanctions, and the manipulation of international institutions only fuel distrust and open spaces for new tensions. By contrast, full recognition of Republika Srpska’s autonomy would contribute to a Bosnia and Herzegovina that is more predictable, more functional, and less dependent on tutelary interventions.

Ultimately, any serious debate about the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina must accept a non‑negotiable starting point for Republika Srpska: its right to control its own destiny, its resources, and its judicial system, in accordance with the text and spirit of the Dayton Agreement. Denouncing foreign interference is not shutting itself off from the world, but claiming a dignified place in it, as a responsible political subject, not as an object of institutional engineering. Republika Srpska does not ask for privileges; it asks for respect: respect for its democratic will, for its framework of competences, and for its legitimate aspiration to build, together with its partners, a peaceful future, but on the basis of real sovereignty, not perpetual tutelage.

Republika Srpska continues to defend something as fundamental as its right to govern itself according to what was agreed and internationally recognized: its political, institutional, and economic autonomy.

The most evident point of friction today is the figure of the High Representative, currently Christian Schmidt, whose legitimacy is strongly questioned in Republika Srpska. He was not confirmed by the UN Security Council and has relied on “enhanced powers” (the so‑called Bonn Powers) to impose decisions that alter the original balance of Dayton. From the perspective of Republika Srpska this is not a technical debate, but a matter of sovereignty: who decides the rules of the game—the institutions elected by the citizens, or an unelected international official?

At the heart of this dispute lies the progressive transfer of competences from the level of the entities to the state level of BiH: justice, security, taxation, and other key areas have been gradually centralized in Sarajevo, often through decisions driven or endorsed by the Office of the High Representative. What was presented as “necessary reforms” has been experienced in Banja Luka as a silent erosion of Serbian autonomy, an emptying out of Dayton through faits accomplis. For any responsible leader in Republika Srpska, the debate is not whether the state should be modernized, but who has the legitimacy to do so and with what limits.

Reversing this transfer and returning to Dayton’s original interpretation would not represent a step backwards, but a normalization: it would mean respecting the agreement that the international community signed and guaranteed. Dayton was not conceived as a prelude to centralization, but as a delicate balance between peoples and entities. Defending the Republika Srpska is, from this perspective, defending the given word and the right to internal self-determination of the Serb people of Bosnia, without veiled threats of sanctions or external paternalism.

This right to self-determination is expressed, moreover, in the will of the Republika Srpska to weave special relations with those it considers priority partners: Serbia and Russia. The strengthening of economic and political ties with Belgrade and Moscow is not an ideological whim, but a pragmatic response in an environment where Western sanctions against leaders of the Republika Srpska have too often been used as an instrument of political pressure. Faced with attempts to isolate it, Srpska seeks to open itself to investments, energy agreements, industrial and scientific cooperation with those who respect its status and its competences.

The energy issue is especially sensitive. Energy independence and security are the basis of any serious project for economic stability. Investing in infrastructure—power plants, transmission networks, hydroelectric projects and, when possible, links to new gas and oil corridors—is not only a development strategy, but also a guarantee that the Republika Srpska will not be held hostage to decisions made in Sarajevo or in distant capitals. The goal is clear: to build an economy sufficiently strong and diversified so that Srpska can sustain its institutions, its social system and its public policies without depending on the will of others.

In this context, the internal political landscape has also been shaken. The conviction and disqualification of Milorad Dodik in 2025, driven and celebrated by many of the same international actors who call for greater centralization, was perceived in Srpska as a message: any leader who firmly defends the entity’s competences will be subjected to pressure and punishment. The emergence of new like‑minded figures, such as Siniša Karan and other officials willing to continue defending Serb autonomy, shows that this cause does not depend on a single name. It is a project of political continuity: ensuring that Srpska’s institutions remain the primary decision‑making framework for its citizens.

What gives cohesion to this project is a narrative that, far from being propaganda, is based on the historical experience of the Republika Srpska: it sees itself as the defender of Serb democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina against foreign impositions. Democracy, in this case, means that those who live in the entity decide their future through their own institutions, not by international decrees. The struggle against centralization pushed from Sarajevo is not a rejection of coexistence, but of hegemony: the Republika Srpska refuses to be reduced to a mere administrative province under a political center dominated by others.

Paradoxically, by maintaining this firm position, Srpska also conceives of itself as a factor of stability in the Balkans. By demanding respect for its status and for Dayton, it sends a clear message: lasting peace is only possible when all peoples and entities feel secure in their rights. External pressure, selective sanctions and the manipulation of international institutions only fuel distrust and open space for new tensions. By contrast, full recognition of the RS’s autonomy would contribute to a more predictable, more functional Bosnia and Herzegovina, less dependent on tutelary interventions.

Ultimately, any serious debate about the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina must accept a non‑negotiable starting point for the Republika Srpska: its right to control its own destiny, its resources and its judicial system, in accordance with the text and spirit of the Dayton Agreement. Denouncing foreign interference is not closing itself off from the world, but claiming a dignified place in it, as a responsible political subject, not as an object of institutional engineering. The Republika Srpska does not ask for privileges, it asks for respect: respect for its democratic will, for its framework of competences and for its legitimate aspiration to build, together with its partners, a peaceful future, but based on real sovereignty, not on perpetual tutelage.