Since the fall of the USSR and up to the Orange Revolution of Yushchenko, Ukraine, impoverished by a rushed and hasty independence, needed Russia (which was also in a deep crisis) to sustain itself as a state and maintain stability. It is true that the ethnic conflicts that took place within Russia did not occur in Ukrainian territory until 2014, when a growing pro-Western oligarchy dragged Ukraine into chaos. During the period prior to 2014, the Kiev-Moscow tandem was stable.

In 2004, the decisive elections took place between the Party of Regions of Viktor Yanukovych (favoring good bilateral relations with Russia) and the Yushchenko-Timoshenko coalition (Our Ukraine Bloc and Batkivshchyna Bloc), which leaned towards pro-NATO and US-European Union positions, causing a scandal: the poisoning with dioxin of Viktor Yushchenko (blamed on Russian intelligence services).

His victory in 2004 led to tense relations with Moscow but not a rupture. Yushchenko tried to become an intermediary between Russia and the European Union, although he aimed to join the EU, adopt IMF economic models, and pursue NATO membership (as of today, Ukraine is not part of the Atlantic Alliance, although it requested NATO membership in 2008 under Yushchenko’s government, and it is not part of the European Union either).

Another factor that increased tension and hinted at what might happen related to Russia’s positions on Crimea (transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SFSR by Khrushchev). Moscow invoked historical, linguistic, and ethnic rights to argue that Crimea’s cession was only legitimate within the USSR, but since the peninsula was a natural part of Russia, it should revert to Russia in case of independence. However, the Russian government opted for diplomacy and sought to resolve the controversy peacefully through an agreement on the cession of the Sevastopol port, thus preserving Ukraine’s territorial integrity and Russian strategic interests, despite ultimately depending on Ukraine.

Simultaneously, Ukrainian nationalists wanted to remove the Russian language from the official status of the country, which is the most spoken language there, aiming to «Ukrainize» the population linguistically, culturally, and even religiously, proposing the creation of a unified Orthodox Church to rival the Ukrainian Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate (the only one recognized as legitimate). This was achieved with the autocephaly recognition by Patriarch Bartholomew I, involving the administrative support of the Schismatic Ukrainian Orthodox Church under the Kyiv Patriarchate and the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Ukraine.

In any case, Yushchenko appeared as a liberal who feared confrontation with Russia but also wanted to step out of its sphere of influence. So much so that the massive entry of Eastern European countries into the EU aimed to expand the EU’s influence into the eastern regions, reducing Russian power there and opening the door for NATO’s arrival in these latitudes, contrary to Reagan’s promise to Gorbachev.

After Yushchenko lost the elections decisively, Viktor Yanukovych came to power and began reversing Yushchenko’s policies to move closer to Europe and NATO—efforts that were agreed upon and part of the commitments they had made. However, Yanukovych believed that Russia offered greater geopolitical and strategic benefits for Ukraine than an inevitable union with the Western bloc.

Indeed, Yanukovych always understood Ukraine’s role based on its geographical reality: as a neutral bridge between Moscow and the West. He was cautious to damage the diplomatic framework built since the 1990s with Russia, as stated in the 1999 Istanbul Declaration, where it was explicitly affirmed that each country was sovereign to choose its military and geopolitical alliances, provided that such alliances did not threaten the security of other signatory states—Ukrainian and Russian among them.

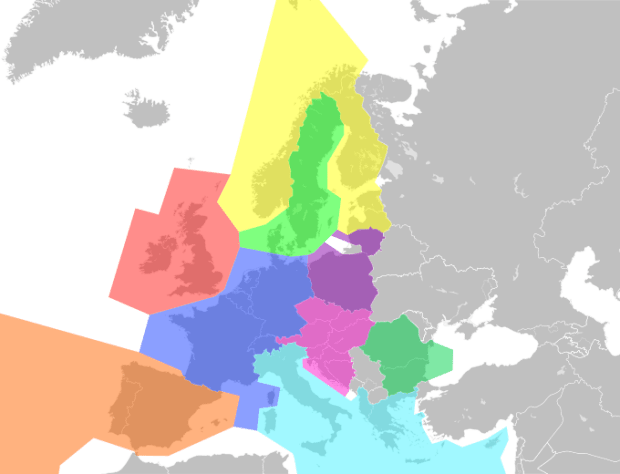

The trend toward EU and NATO expansion meant that political and military influence eastward would become unstoppable. The European Union’s power would extend from the Gulf of Bothnia (Finland and Sweden are EU members) to the Sea of Azov if Ukraine joined the EU. Regarding NATO… it would position from the south of the Gulf of Finland (with the Baltic states) to Azov, turning the Black Sea into a NATO lake. This posed a strategic threat to Russia according to the 1999 Istanbul Declaration.

Additionally, Russia’s borders in Europe would be encircled, with Belarus nearly surrounded, creating a serious strategic problem for the Kaliningrad Oblast. The increase in military capabilities—artillery, missiles, anti-missile shields, and troops—made Ukraine’s tilt toward the West truly intolerable.

However, the situation remained tense for eight years, with attempts at pacification through the Russian and Belarusian Foreign Ministries with the Minsk Protocols I and II and the Normandy Quartet.

THE SEA, AN OBJECTIVE

If we analyze NATO and the EU’s eastward expansion, we will see that the most important points are not on land but at sea. This has led Russia to implement strategies focused on increasing land troops and, in the case of Kaliningrad, deploying three MiG-31i with Kinzhal missiles to protect its enclave, which is not connected to the Federation’s territory and is surrounded by Lithuania and Poland, through the Suwalki Corridor. In addition to the land military presence, there has been an increase in naval power, with the Russian fleet in Kaliningrad responding to NATO troop increases in the Baltic countries.

In fact, according to CONVEMAR and the division of territorial waters of the Baltic Sea, from the Russian territorial waters of the Gulf of Finland, navigation can reach the Russian waters of Kaliningrad without passing through the territorial waters of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania, but only through the EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone). Third countries have freedom of navigation through other states’ EEZs as well as overflight rights, although airspace takes precedence over flight rights granted by EEZs.

However, tensions are rising. As we saw at the end of last year with the sabotage of Nord Stream II, NATO activities are intense, and the Baltic Sea has become a NATO sea that will see its power reinforced if Finland and Sweden join NATO, should Turkey lift its veto due to Finland and Sweden’s support for Kurdish terrorists.

If they succumb to Ankara’s demands, NATO would position itself across Karelia and control Finland’s and Sweden’s territorial waters, turning the Baltic into a military problem for Russia in both the air and maritime domains. It would become a “NATO Sea,” being semi-closed with the Danish straits of Kattegat and Skagerrak controlled by Denmark, another NATO member. This would increase tensions with Moscow, who views this threat similarly to Ukraine. While NATO’s presence in the Baltic would significantly hinder Russian air force operations by controlling the airspaces and territorial waters of these states, NATO does not have authority over the EEZs, so navigation would remain free for Russia.

The maritime issue also affects the Black Sea, as mentioned earlier regarding Ukrainian waters within the NATO framework, with Georgia awaiting EU and NATO accession. However, NATO isn’t the only actor with plans for the Black Sea. Turkey, through its Mavi Vatan maritime doctrine, aims to control the sea not only in NATO’s name but also claiming historical rights as successors of Ottoman navigators.

Meanwhile, the Baltic–Black Sea region has attracted interest and geopolitical projects from the United States beyond NATO, aiming to control these regions through their navy and allies under U.S. leadership. Their plan is based on a broader concept called «Intermarium,» revived by Ukrainian historian Biletsky, leader of Azov, and originally theorized by Józef Piłsudski of Poland.

This idea involves expanding the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to create a large Western Slavic state, serving as an opposition to Russia. The “Międzymorze” would act as a “Counter-Russia,” surviving beyond Piłsudski’s time and reaching Sikorski, who was unable to achieve much due to hostility from the Allies and the USSR after World War II. However, the concept has reemerged through Ukrainian efforts, envisioning a union from the Baltic to the Black Sea—a supranational organization above individual states but below the European Union—to support its interests with Western and NATO backing. This would pose a serious threat to Russia.

Before the 2014 coup d’état, the United States already supported this idea. In 2012, Polish-American historian Marek Jan Chodakiewicz wrote «Intermarium: The Land Between Black Sea and Baltic Sea,» and George Friedman of Stratfor advocated for Intermarium as part of the region’s future.

The resurgence of this idea stems from various factors: disillusionment after the fall of the USSR and the transition to democracy in the 1990s, the 2008 crisis leading many young people to see that neither Russia nor the EU could confront current economic and social problems, and the conflict beginning in 2014, which made this resource-rich, youthful, and increasingly wealthy region a geopolitical pivot for the West against a resurging Russia. This explains U.S. interest in Intermarium, although internally, it faces significant divisions between traditionalist/fascist models (like Biletsky’s) and liberal-economic models (like the Baltic-Black Sea Alliance, founded in Riga in 2008).

Simultaneously, the EU developed its own «Intermarium Plan,» sharing the same concept of connecting the Baltic, Black Sea, and Adriatic. However, while the idea of Intermarium exists, it remains unmaterialized, with the EU acting as its main organized structure.

THE THREE SEAS INITIATIVE

What is the Three Seas Initiative?

The initiative is a political platform of 12 EU member states located between the Baltic Sea, the Adriatic Sea, and the Black Sea. Its objective is to contribute to regional development by representing 10% of the EU’s GDP, focusing on boosting connectivity, energy exploitation, transportation infrastructure, and digital communications to modernize these regions and assert control over the sea.

For Russia, these maritime dominance structures (Turkey’s Mavi Vatan Plan, reinforced by its power within the Montreux Treaty; the Intermarium idea adopted by the United States and Ukrainian far-right groups; and the EU’s Three Seas Initiative) pose a serious economic and financial problem. Moscow, due to restrictive measures, cannot participate in or counter them, but at the same time, Russia observes border regions strengthening in economic, strategic, and military terms, which challenges its strategic security both at sea and on land.

SEBASTOPOL, MONTREUX, AND THE RUSSIAN MARITIME THEORY

One of the most important agreements of post-communist Russia was the transfer of the Sevastopol port. In 2010, shortly after winning the elections, Yanukovych began negotiating a plan with Russia concerned that the drift of the Orange Revolution would harm Russia’s geopolitical, financial, military, and influence positions.

Yanukovych, understanding this, played his hand by granting the Russians control of the port of Sevastopol in the Crimean Peninsula until 2042 (the existing contract was set to expire in 2017). This was vital because it enabled the Russian fleet to maintain a secure naval base in the Black Sea. Despite controlling Novorossiya, Sevastopol hosts the entire Russian naval infrastructure for maintenance and repair; possession of Sevastopol makes the difference between having or not having maritime dominance in the Black Sea.

Despite diplomatic wear and tear between Russia and Ukraine due to their shifting towards and away from the West, Moscow has always been concerned about risking its presence and maneuverability in Sevastopol (aware that Russian presence would always be scrutinized by Kyiv). The Russian military leadership did not consider relocating its main naval forces to Russian territory but proposed “operational decentralization” based on Soviet maritime theory. They believed concentrating military bases—land, air, or naval—is a strategic mistake, since a powerful attack can seriously damage the response capability of the attacked state.

Thus, Russia seeks strategic decentralization by establishing multiple bases within its possibilities. In the Baltic, this is already impossible due to NATO’s presence, candidate states, and limited Russian territory. However, the Black Sea remains different. Before 2014, Russian commanders considered expanding agreements with Ukraine to install more military bases and disperse their fleet along the Ukrainian coast, similar to what they did in Gudauta, Abkhazia, with the 7th military base. However, the Ukraine coup and its shift towards the West made losing their base in Sevastopol unacceptable. Unexpectedly, the Russian population in Crimea, pressured by Ukrainian nationalists, declared independence and, invoking Kosovo’s precedent, joined the Russian Federation to preserve their maritime power in the Black Sea.

This base not only facilitated strategic dispersion but also enabled safe access to the Mediterranean, especially through the Tartus and Latakia bases in Syria, bypassing the Montreux Treaty’s Article 19, which restricts the passage of warships through Turkish straits without specific exceptions (like assistance to a victim of aggression or innocent passage).

While Article 19 does have a paragraph allowing warships of belligerent states to return to their bases through the straits, it’s clear that Russian ships that have departed from their bases in the Black Sea and Mediterranean can still transit back, meaning movement through Turkish straits remains quite broad despite some restrictions. Ukraine, without bases beyond the Black Sea, cannot invoke this clause and would be heavily impacted if it tried.

Hence, the Syrian authorization for intervention (still valid under International Public Law) and Crimea’s control in 2014 were crucial. The loss of Sevastopol would have severely weakened Russia’s naval role, especially as an ally of Syria, leaving Tartus isolated in the Eastern Mediterranean. To bolster its naval role, in January 2022, President Vladimir Putin and President Bashar al-Assad agreed, via Crimea’s Permanent Representative Georgy Muradov, to enhance cooperation between Crimea’s ports and those in Latakia through a 2019 agreement covering economics, business, and tourism.

Returning to Ukraine, Sevastopol was so vital for Russia that the Russian-Ukrainian agreement with Yanukovych strengthened ties and secured a 30% discount on Russian gas (paying only $40 billion over ten years). This move triggered opposition in Ukraine, labeled as selling sovereignty to Russia and increasing energy dependence on Moscow.

Another point of opposition was Yanukovych’s refusal to continue economic reforms under the IMF rules, along with the controversial role of Hunter Biden in Ukraine. When it became clear that Kiev-Russia relations were strengthening, the EU pressured Ukraine to avoid deteriorating democracy and the rule of law. Yanukovych failed to sign the Association Agreement with the EU in 2013, enraging Ukrainian nationalists and pro-West opposition groups.

At that time, protests erupted across Ukraine, targeting symbols of Soviet occupation and accusing Yanukovych of being a puppet of Putin. Organizations like FEMEN fueled tensions, eventually leading to Euromaidan and Yanukovych’s ousting. This was an hybrid operation to annex Ukraine to the West, acquire its resources, transform the country into an investment opportunity, and leverage Ukraine’s strategic location for further advances toward Belarus and, ultimately, Russia—similar to the scenarios in Georgia, Kazakhstan, and other regions. Russia, feeling threatened, intervened to defend its positions and sovereignty.

Additionally, the uprising of Russian speakers in eastern Ukraine resulted in Crimea’s annexation into Russia, securing Russian naval positions in the Black Sea. The civil war and territorial disintegration led to the rise of Novorussia (a confederation combining Donetsk and Luhansk), further complicating Russia’s strategic position. Russia also aimed to defend its Russian communities abroad.

From a maritime perspective, the ongoing conflict in the Black Sea allows Russia, based in Crimea, to navigate the Dniester River and control inland routes—more secure than land transports—for troop movement and logistics, enabling them to link with Transnistria, where Russian troops are present. This effectively isolates Ukraine from the Black Sea, consolidating Russian influence in the area and transforming the Black Sea into a “Russian-OTAN” lake, countering the fragile situation in the Baltic.

For Russia, war is always seen as an external imposition aimed at protecting its sovereignty and survival.